|

Index...

|

n 1977 it was the Queen's Silver Jubilee, and everyone was encouraged to join in the celebrations. Coventry Working Men's Club in Cox Street had just opened their rebuilt new club and asked if the Queen would like to visit.

n 1977 it was the Queen's Silver Jubilee, and everyone was encouraged to join in the celebrations. Coventry Working Men's Club in Cox Street had just opened their rebuilt new club and asked if the Queen would like to visit.

This must have caught the eye of the staff at Buckingham Palace as a novel idea and an un-excepted invitation. It would also be the first time the Queen had stepped into a Working Men's club. It would be the only visit to Coventry that she would taking that year, so when the Lord Mayor Councillor Ralph Clews found out, he wanted to be part of it and meet the Queen. He wanted Coventry to give her a good welcome and for him to give her a true representative present, so he called together any council officers who had any good ideas to a meeting in his office.

One of the officers was Peter Mitchell, Keeper of Industry at the Herbert Art Gallery and Museum. At the Lord Mayor's meeting Peter Mitchell suggested a special leather-bound book of Coventry's motoring heritage that could be presented to the Queen by the Lord Mayor, plus for all the vehicles in the book to be on show that day. His idea was that the Royal Car and convoy would go on a route past the Council House, then turn into Bayley Lane and past the New Cathedral, where opposite would stand a line of fifty vintage vehicles from the Museum's collection. The Royal Car should travel slowly, so both the Queen and the Duke of Edinburgh could see the Cathedral on one side and the line of vehicles the other. The Royal car would then go down Priory Street, right into Fairfax Street, and right again into Cox Street for the Working Men's Club. The Lord Mayor liked the idea and gave the go ahead, but the problem was that the Queen was going to visit in six weeks time. This problem was left for Peter Mitchell to sort out.

I first meet Peter when he joined the Herbert Museum in the mid 1960s. He had moved from the London Science Museum to take over looking after Coventry's collection of industrial items. But he had a problem, which was that nearly all his collection was in storage and no one know about them - except for a few cars and cycles in the Herbert Museum main gallery - but nothing like the full collection. He was a very enthusiastic and persuasive man, it seemed like he hovered two inches above the ground, always very busy but infectious with his ideas and vision.

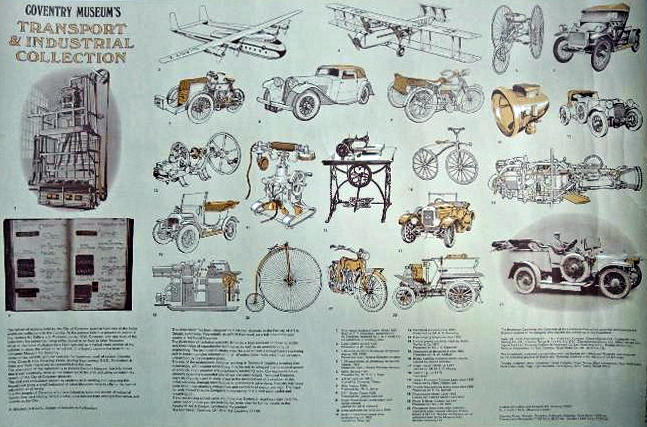

He came to the Coventry Art College and asked us students if we would like to draw some of the items in the collection. There were only eight of us in the Technical Illustration course but we were all very keen. The industrial collection was not far away - it was in a old ribbon-weaving factory in Much Park Street known as "Franklin and Sons". The offices faced onto Much Park Street through a wooden gate and arch into a cobbled court yard, and standing there was the wonderful ribbon factory just like the one by the Priory Ruins (now Nando's). Inside this factory was an amazing collection of everything you could think of - weaving looms, cars, motorcycles, bicycles, sawing machines, telephones, radios, engines, and machinery of all sorts - a true Aladdin's Cave! We did various drawings around the building and a fact sheet was produced to be sold in the Herbert Museum shop.

Please see the photograph of the sheet on the left. It was designed to be either a poster, or be folded down to hand size. I did the drawing of the 1880 Humber High Ordinary Penny Farthing cycle, the Hay-fork Ladies Tricycle, the 1904 Riley Tri-car, the 1871 Europa Sewing Machine made by Smith, Starley & Co., and the Hand Ringing Telephone, circa 1900.

Not long after this photograph was taken most of the street was knocked down, and the museum collection in the Franklin building was moved to an industrial estate in Till Hill.

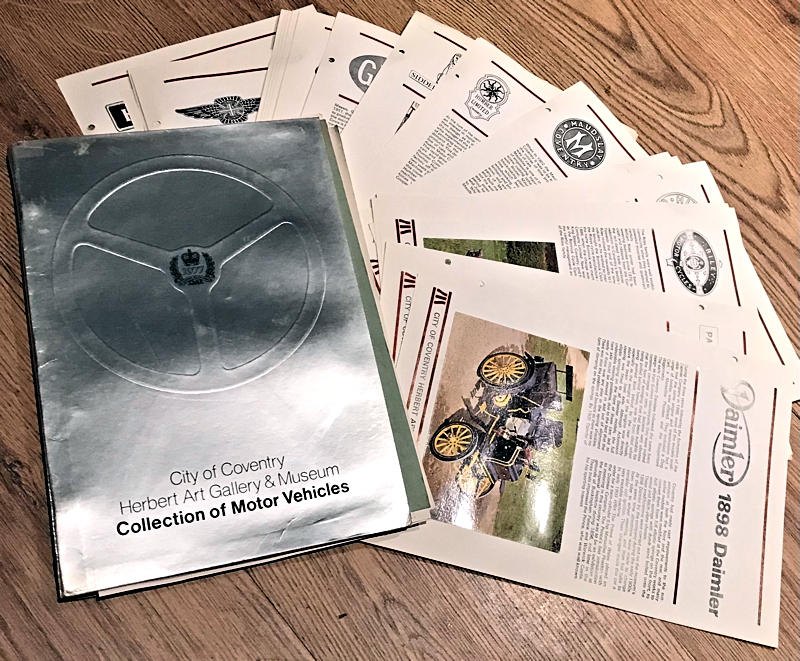

So, when Peter Mitchell came up with his idea of writing a book, having it printed and bound all in six weeks, and to be self financing, this was a challenge. A special plan was set up, as a one-off book would cost a fortune. The idea was to produce a fact-sheet for each of the 50 vehicles. The fact-sheet would have two sides, and on each sheet would be a space for a colour postcard of the vehicle, which would be pasted into a space - a bit like collecting stamps. The book contained 50 pages, each on a different vehicle starting from the 1897 Daimler to the 1976 E-Type Jaguar. It had other pages, too - the introduction, a note from the Lord Mayor, and other information. Only 500 were printed. (A large number of colour postcards were also printed to keep the cost down, but they were sold separately.) After taking one sheet each to make up the Queen's book, the rest of the sheets had holes punched in the side and would be put into a clip folder, which would be sold to the general public.

We started on the postcards straight away, as they would need to go for colour printing, so we had to take each vehicle out of the store and clean and photograph it. I was given the task of having to draw some interesting feature from each vehicle. Also, for each sheet a vehicle badge had to be drawn to go on the top of every page. The job was a rush but it was all completed in time for the Royal Visit. The line of fifty vehicles lined up opposite the Cathedral caused quite an interest, as they were put out very early in the morning so they would be in place for people to see while waiting for the Queen's visit. It did catch the eye of the Coventry and Warwickshire Chamber of Commerce, who said they did not realise that the Herbert Museum had so many vehicles, and when they were told it was only half of the collection of vehicles they were really surprised, and suggested they could help and open a special museum for the collection. So, over the next few years the Chamber of Commerce members raised a lot money for a building in the city centre. One was found - the building that used to be the steel fabrication part of Matterson's, Huxley & Watson's - at the back of the Coventry Theatre in Cook Street.

A quick business plan was set up that said if the museum was to charge an admission charge it could be self-funding! This was based on a few facts, like Coventry Cathedral having around two million visitors a year. If the new Transport Museum was to get just 5% of them it would still get around 75,000 to 100,000 a year. What had not been taken into account was the fact that visitors to the Cathedral did not pay to get in, and most were only visiting for an hour before moving on to Warwick or Stratford.

ork started on restoring the Cook Street building and making ready the new museum, to be opened in 1980. Things got difficult when Peter Mitchell was offered a better job working for British Leyland Heritage to set up a new Museum for them and their collection of vehicles, and as the money and position was better Peter left about a year before the Transport Museum was to opened. It was good luck that Barry Littlewood, the Administrator of the Libraries, Arts and Museum Department, was able to take over from Peter. Barry turned out to be the best boss I ever worked with - he gave me support and flexibility, and in return I worked evenings and weekends constantly.

ork started on restoring the Cook Street building and making ready the new museum, to be opened in 1980. Things got difficult when Peter Mitchell was offered a better job working for British Leyland Heritage to set up a new Museum for them and their collection of vehicles, and as the money and position was better Peter left about a year before the Transport Museum was to opened. It was good luck that Barry Littlewood, the Administrator of the Libraries, Arts and Museum Department, was able to take over from Peter. Barry turned out to be the best boss I ever worked with - he gave me support and flexibility, and in return I worked evenings and weekends constantly.

It was not all plain sailing, though. The City Council Committee for Libraries, Arts and Museums, who were responsible for the museum, had a problem with the Museum's name. They felt that people would think the museum would be only display Coventry Transport items like buses! City Councillors were used to Coventry Transport being about public transport, and if you know what it's like working with a committee it's very difficult to stop them from over-thinking everything. (It's a bit like asking a committee to design a horse - they will come up with a camel!) The committee wanted a name that told you what the museum was about. So, some member said the collection does not have any boats, planes or trains in the collection, so you cannot call the museum 'transport' on its own - so 'road' was to be added. Some transport museums had foreign vehicles but Coventry had mainly Coventry or British made vehicles, so 'British' was added. The name they came up with was 'Museum of British Road Transport, Coventry'. We tried to get them to change it to 'Museum Of Transport Of the Road' so the initials would spell out 'MOTOR', but the committee got their way.

Next, the committee picked an admission price for the Museum. They found that the London Transport Museum, which had just moved to Covent Garden, was charging a £1 for adults 50p for children, and the National Transport Museum at Beaulieu was charging £1.20 for adults and 60p for children. Don't forget, this was 1980. The committee did not take into account that the Glasgow Transport Museum and the Birmingham Industrial Museum were free. The Coventry price was going to be £1.10 for adults and 55p for children. We asked them to lower it - Coventry is not London, and people are not used to paying to get into museums - but they were not moved.

The next headache was that we wanted a famous person to open the museum to get publicity, but the committee said it should be the Lord Mayor. The Museum was going to be opened on the first Saturday in September, so the opportunity of getting visitors over the summer holidays was missed because the councillors wanted to be at the opening, but they would be on holiday so things had to be put back. Posters had been printed - then the Lord Mayor said he could not make it on that Saturday, so it was quickly changed to Sunday afternoon. You can imagine what a great start (or damp squib) the Museum's opening was like!

To begin with, the Transport Museum was not a big success. People did not flock to the doors because they could not find their way to Cook Street, or the admission price put them off. The manager of the De Vere Hotel said that American visitors would love to come and visit, but they would not walk up Chauntry Place or around the back by the Parson's Nose chip shop, as both were dark, dirty and narrow entrances to Cook Street. It was not until 1986, with a new entrance opening onto Hales Street, that things started to pick up.

But it was great that it had all started out from the Queen's visit to a working men's club. Sadly, the club is now closed and gone, there are no old-style working men to go to such a club, but the things that they made are on display in the Coventry Transport Museum, which is still going from strength to strength. We got the name we wanted and the free museum entrance in 1998. Nothing stays the same, though. New management took over after Barry Littlewood retired, and after a few years and using consultants to do the job that I used to do I was made redundant.

I believe that all museums and art galleries should be free - they bring in visitors and give the city pride in its past. But due to cuts and other thinking, the Transport Museum is back to charging (2022 prices Adults £14, Concession (Senior & students) £10.50p, Junior (5-16 years) £7. Children 4 years or under free. Family Ticket (2 adults + 2 children) £35, or Small family (1 adult 3 children) £28). If you have a 'Go CV' card you can get in free.

The last time I visited the Museum it was empty, no longer a bustling place. I fear for its future, and now the Ikea building needs filling, so I can see most of the collection going into storage. What do you think - should we be charging for admission, or should we be opening up our treasures, not trying to making a quick buck out of the visitors?

See photographs of 1980 just before the museum opened. It's me in front of the vehicles - with the two fact-sheet pages from the Queen's book on a stand in front of each vehicle. The other photograph is me on the left in the new museum shop, which was the first thing you saw when walking in the main entrance from Cook Street. Barry Littlewood the manager is on the right. The museum opened the next day.

Read Paul's next excellent Transport Museum article about the New Hales Street Entrance in 1985.

Website by Rob Orland © 2002 to 2026