|

Index...

|

John Corbett Arnott aged 15.

Elsie Ansell aged 21.

Rex Gentle aged 30.

Gwilym Rowlands aged 50.

James Clay aged 82.

n 12th January 1939 the Irish Republican Army, claiming to be the "Government of the Irish Republic", issued an ultimatum to the British Government. It gave them four days to withdraw all British armed forces stationed in Ireland and declare that they would renounce all claims to interfere in Irish domestic policy. If they received no response, they said they would be compelled to intervene actively in the military and commercial life of Great Britain. Four days passed with no reply so a campaign known as the "S-Plan" was launched against Britain. This mainly involved bombing commercial premises, sabotaging electricity supplies, blowing up telephone kiosks, public lavatories, mail boxes and railway stations. Coventry was mentioned by name in the I.R.A. plans, which had singled out its electricity supply as a prime target. Civilians were not supposed to be targeted.

n 12th January 1939 the Irish Republican Army, claiming to be the "Government of the Irish Republic", issued an ultimatum to the British Government. It gave them four days to withdraw all British armed forces stationed in Ireland and declare that they would renounce all claims to interfere in Irish domestic policy. If they received no response, they said they would be compelled to intervene actively in the military and commercial life of Great Britain. Four days passed with no reply so a campaign known as the "S-Plan" was launched against Britain. This mainly involved bombing commercial premises, sabotaging electricity supplies, blowing up telephone kiosks, public lavatories, mail boxes and railway stations. Coventry was mentioned by name in the I.R.A. plans, which had singled out its electricity supply as a prime target. Civilians were not supposed to be targeted.

Memorial to the Victims, Unity Lawn, Coventry Cathedral.

Memorial to the Victims, Unity Lawn, Coventry Cathedral.

Unless you have a reasonably good knowledge of local history the five names at the start of this article will probably not be familiar to you. They were the victims of the worst terrorist attack Coventry has ever suffered. On 25th August 1939 all of them had the misfortune to be in Broadgate. It was a busy Friday lunchtime. Elsie Ansell, a shop assistant at Milletts in nearby Cross Cheaping, was on her lunch break and may have been looking at jewellery in the H. Samuel shop. She was due to be married a fortnight later and invitations to the wedding had been sent out that week. Gwilym Rowlands, known as Bill to his colleagues, was a road sweeper. He and his workmate (John Worth) were working outside Astley's and Burton's shops. John Arnott and Rex Gentle both worked at W. H. Smith and Son in Hertford Street and were returning after their lunch break. Rex had changed his lunch hour so he could spend it with John. James Clay had left a meeting at a nearby cafe with a business friend earlier than usual due to not feeling well. This was the first time in six years the two friends had not left at the same time. Around 2:30 pm these people and many others were in the vicinity of Astley's shop when the normal hustle and bustle of the city centre was shattered by an I.R.A. bomb.

Ironically, in the city that is regarded as its British birthplace, a bicycle played an instrumental part in the mass murder and carnage that shocked the nation.

A typical Broadgate day in 1939 - just as it would have appeared shortly before the tragic event of August the 25th.

A typical Broadgate day in 1939 - just as it would have appeared shortly before the tragic event of August the 25th.

On Tuesday 22nd August 1939 James McCormack (alias James Richards), the leader of the I.R.A. unit operating in Coventry, accompanied another unknown I.R.A. man to the shop of the Halford Cycle Company in Smithford Street. McCormack waited outside while the other man purchased a Halford 'Carrywell' - a tradesman type cycle built for Halford by the Birmingham Bicycle Company which had a carrier basket to the front of the handlebars. He gave a false name and address - Mr Norman, 56 Grayswood Avenue, Allesley Old Road, Coventry - and paid a deposit of £5 - pledging to pay the remaining 19s 6d on collection, which would be either Friday or Saturday. On the morning of Thursday 24th August 1939 another I.R.A. man began constructing the bomb at 25 Clara Street, Stoke, Coventry. The house was being rented from Loveitt & Sons by Joseph Hewitt who lived there with his wife Mary, their baby child Brigid Mary and his mother-in-law, Brigid O'Hara. After marrying his wife at St. Peter's Cathedral, Belfast, in August 1935, Hewitt came to Coventry in 1936 to find work. His wife and mother-in-law soon followed. Their baby was born in Coventry in 1938. They moved to Clara Street from Meadow Street, Spon End in June 1939. James McCormack lodged with them. It was used as a 'safe-house' for the I.R.A. where McCormack had constructed a concrete storage pit under the stairs a few weeks earlier to store explosives. Joseph Hewitt may not have been a member of the I.R.A., but he clearly had strong sympathies towards it, and was happy for his family home to be used in this manner despite of the risks this entailed. That evening, at around 7:00 pm, a Transport Officer in the I.R.A. called Peter Barnes arrived at the house from London. He had travelled by train and brought with him potassium chlorate to be used as the explosive in the device. Barnes' role in the I.R.A. was to ferry explosives from their main ammunition dumps in Liverpool and Glasgow to their operatives across the country. He left later in the evening and returned to London.

The bomb maker completed his task the following morning. It was a 5lb device with an alarm clock used as the timer. The bicycle was collected from Halford's by McCormack at 12:30 pm and left in the back lane (known as a jetty) at the rear of the house around 1:10 pm. By this stage the bomb had been parcelled up in a box that was wrapped in brown paper and tied with a string. The bomb maker placed it in the carrier basket and began his journey into town. Sometime between 1:30 and 1:45 pm the bicycle with its deadly cargo was left standing against the kerb outside Astley's shop where it was to shortly explode with such devastating consequences.

Many victims of terrorism or political conflict are totally forgotten about once the initial outrage or shock has died down. Just a week or so after the Coventry bomb, Great Britain declared war on Germany, and a year or so later our city was to suffer carnage on a much greater scale with the blitz of 14th November 1940. Perhaps these events helped play a part in effectively 'burying' the tragedy that took place in August 1939 for the next 76 years?

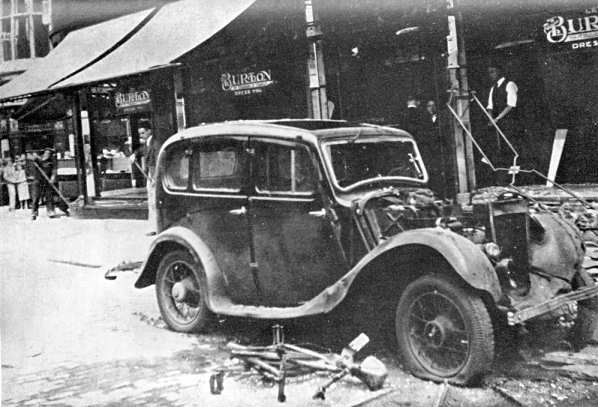

Part of the carrier cycle lying in front of the damaged car.

Part of the carrier cycle lying in front of the damaged car.

An excellent book called "Lost Lives" was first published in 1999. It attempts to record all those who died in the Northern Ireland 'Troubles' from the 1960s through to the ceasefires of the 1990s and beyond. It is an incredibly poignant and moving book which had me in tears on several occasions. Below I give a few details of Coventry's "Lost Lives" which were gleaned from contemporary newspaper reports and kindly provided by relatives:

Elsie Ansell, of 13 Clarendon Street, Earlsdon, was the daughter of Alfred Ansell and Laura Henrietta Ansell (née Lever). She had one brother, called Frederick but known as Fred. Her father died when she was just 16. The explosion killed her instantly and caused horrific injuries to her body. These were so bad that she could only be identified from scraps of her clothing and engagement ring. William Charles Blake, the manager of Milletts, performed this sad task. He had noted Elsie had not returned from her lunch break, and then received information that she had been caught in the blast. So he made his way to the mortuary where his worst fears were confirmed. Some newspaper reports say that her fiancé, Harry Davies, rushed to the mortuary too but was not allowed to see her decimated body.

Instead of being married at St. Barbara's Church to Harry on September 9th, her funeral service took place there instead on August 30th. On top of her coffin was a spray of cream roses with a card that read "With everlasting love and remembrance, from your husband to be Harry." The two children who were to have been bridal attendants - Joyce and Bobby - sent a basket of pink carnations, and a wreath of white chrysanthemums from her mother Laura bore the inscription "With treasured memories of a most beautiful and devoted daughter".

Other floral tributes included ones sent by her work colleagues at Milletts, the Albany Social Club (three in total - from the club itself, the staff of the club, the lady members of the club) and poignantly from Elsie May Arnott - the mother of John Arnott.

The six coffin bearers were also from the Albany Social Club, which to this day can still be found at 10, Earlsdon Street. Elsie's family had strong connections to it. Her parents appear to have been the Steward and Stewardess in the early 1930s and her mother was working behind the bar in 1939.

A crowd of 600 to 700 people, mainly women, were at London Road cemetery to see her laid to rest. Many wept as the coffin was lowered into the grave. She was buried in what would have been her wedding dress.

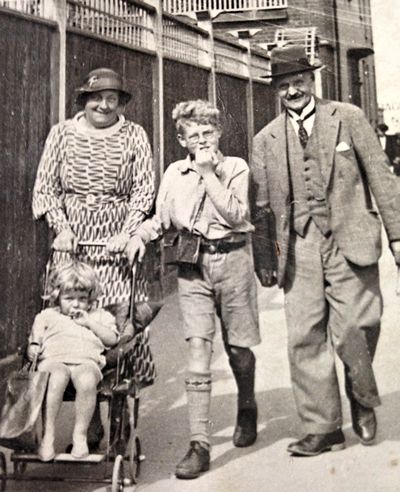

John Arnott with his parents and sister Mary.

John Arnott with his parents and sister Mary.

John Corbett Arnott, of 12 Daimler Road, Radford, was the youngest victim of the atrocity. His parents were William Thomas Arnott and Elsie May Arnott (née Corbett). His father had died the previous November aged 64. His sister Mary was only 7 when she lost her brother.

After leaving Radford School, John worked for W. H. Smith and Son. With his mop of curly hair and glasses he was a familiar face to many Coventrians through selling newspapers and magazines at the store. At first it was thought his body was actually that of a Mr Hollander of Coundon Road as young John had a bill in his pocket for this man which he was due to deliver.

He was buried at London Road cemetery on August 29th with around 100 mourners in attendance. These included Mr. L. Galsworthy and Mr. A. A. Walker who were members of staff at Radford School. Mrs Ansell and Harry Davies sent a wreath, as did the family of Rex Gentle.

On August 30th the Midland Daily Telegraph published this letter from John's mother:

Dear Mr Editor,

Will you please print my thanks where you will, but I feel I would like to put into print my thoughts as well. The doctors and nurses tried to save my boy's life but God said "No."

The kind thoughts of the people go to help me bear my cross. We all have a cross to bear, and when I look at others' plight, I feel my cross is only light.

To the kind nurses who took me to kiss him "Good-bye," thanks, and I'll always remember the youngest nurse's sweet face. God gave me these words in the loneliness of the night when his little sister was sleeping by my side. Once again thanks for all your kindness, I'll never forget.

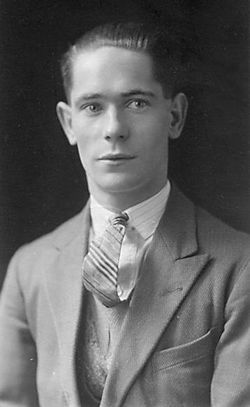

Rex Gentle was born on 3rd April 1909 in Newtown, Montgomeryshire in Wales. The son of Richard and Margaret Gentle (née Jones), he was an identical twin and engaged to May Jones. The family home in Newtown was at 6 Frolic Street. He was employed by W. H. Smith and Son as a Trainee Manager, initially in Newtown, and was then sent by the company to work in various places providing relief cover. In 1938, he worked at their Rugby shop and became well known to many people in the town. A Baptist, he worshipped at the church in Regent Place and lodged with Mrs. Clowes at 12, Duke Street. Reports suggest he left Rugby in the early part of 1939.

In August, Rex was assigned to work at the Coventry store which was located at 62 Hertford Street. He lodged with the Arnott family at 12 Daimler Road, and had been working in the city for two weeks when his life was cruelly ended. It is believed that he changed his lunch hour on that fateful day so both he and young John could eat at the same time at the Arnott family home - thus saving Mrs Arnott the trouble of having to prepare separate meals at different times. It was an act of kindness typical of Rex. Some newspaper reports suggest that he lost his life on what was meant to be the last day of his employment in Coventry before taking up a similar role at the Warwick store.

Rex Gentle.

Rex Gentle.

On the day of the explosion, his twin brother Jack was working in Newtown. In the afternoon he was sent home from work suffering from a severe headache. It is often said that when one identical twin suffers pain the other can feel it - Rex had indeed suffered severe head injuries.

After the explosion, word reached the Gentle family in Wales that Rex had been badly injured in an incident in Coventry. His parents could not travel so his twin brother Jack and his wife Rene made the unenviable journey to Coventry. On the train, Jack turned to his wife and told her that he knew his brother, who he was very close to, was dead - again, when he said this it turned out to be almost to the minute that Rex did pass away. When the couple arrived in Coventry a trial blackout was in operation in preparation for the probable forthcoming war with Germany. They could not find the hospital so approached a policeman, who, knowing about the bomb, took them there. Jack was needed to identify his brother but apparently passed out, so his wife Rene carried out the traumatic task. The body was covered in bandages and she identified Rex by his mouth. While they were at the hospital the manager of W. H. Smith and Son paid a visit and had an almighty shock when he saw Rex's identical twin brother Jack - he thought it was Rex! The same thing happened when a sister of the twins in Birmingham was visited. Jack and Rene called on her to break the bad news. She opened the door with, "Hello Rex! What are you doing back here?" Jack explained that he wasn't Rex and informed her of what had happened in nearby Coventry.

Jack and Rene Gentle returned to Birmingham for the Coroner's inquest into the deaths. The report of the injuries suffered by the victims was so bad that Rene arranged for their relatives to be able to choose to leave the room while it was read out. She stayed and Jack left. Despite asking her about what she heard she never told him - the injuries being so horrific.

In 1966 the husband of Jack Gentle's daughter Marie was shown round the police museum at Little Park Street where the remains of the bicycle and some of the evidence gathered during the investigation are kept in a simple glass cabinet. It must have been an upsetting experience to say the least.

Rex Gentle, who was much loved by his family and fondly remembered by them to this day, was buried in Newtown after a service at the local Baptist church conducted by the Rev. D. H. Thomas. Those in attendance included Mr F. H. Davies, Manager of the Newtown branch of W. H. Smith and Son. Elsie Arnott sent a wreath as did the Manager and Staff of W. H. Smith and Son in Coventry.

Gwilym Rowlands, of 121 Beake Avenue, was born in Nantyffyllon, Maesteg, Wales. It is highly probable that he was born on 12th November 1887 which would have made him 51 and not 50 when he died - but all newspaper and official reports after the incident state he was 50. His parents were William and Margaret Rowlands (née Bowen). His father died when he was very young. In 1912, he married Mary Ann Morris at Llanyrnewydd church. In Wales, he had been a coal miner and as a young man had worked at Blaengwynfi colliery. He moved to Coventry from Cwmavon Road, Aberavon, Port Talbot and is said to have been a popular member of the Port Talbot Progressive Club.

He had made Coventry his home on the advice of his son William, who had relocated here some years earlier. He too had been a collier, and when he saw a close friend die in an accident at a pit, he decided enough was enough and made a new life for himself in Coventry - in 1939 he was a machine tool setter. Worried that his father would meet the same fate as his friend, he encouraged him to make the same journey and take up a new profession. It was a decision that would haunt him as he wrongly blamed himself for his father's death. He would not speak about his dad or the bombing for the rest of life and visited his grave on his own to lay flowers.

Gwilym had been employed by the Highways Department for four years and some reports suggest he was nearing the end of his shift when the bomb exploded.

His wife Mary Ann received no compensation from the authorities for the loss of her husband and instead was offered a job with the Coventry Corporation (now known as Coventry City Council). After the explosion, she had the grim task of identifying his body at the public mortuary.

His funeral service took place at St. Nicholas Church, Radford, which itself would be destroyed in the 14th November 1940 blitz. A large crowd of mourners were in attendance, including his wife, son William, daughter May, and one of his brothers - Sydney - who had travelled from Wales. Two friends of his son walked all the way from Port Talbot to pay their respects and many people from Coventry's large Welsh community also attended. A party of his former colleagues from the Highways Department, dressed in their work attire, stood near the church until the cortege arrived. Led by their foreman J. Walker, they then left their street cleaning equipment outside and joined those inside.

The Rev. F. S. Herbert conducted the service and spoke the committal words when his body was interred in the adjacent graveyard. Floral tributes included wreaths from the Radford Social Club, Transport & General Workers Union, Workmates of the Cheylesmore Depot and neighbours and friends at Beake Avenue.

At the time of his death, his elderly mother was residing at 42 Dyffryn Road, Caerau, which was the home of his brother Sydney. She passed away not long after Gwilym in November 1939 aged 86. A grandson, also called Gwilym Rowlands, attended her funeral.

James Clay, the eldest victim, was a widower and grandfather who lived at 22, Clarendon Road, Kenilworth. He was a well known and popular Coventry character. Born in 1857, he was the son of Joseph and Catherine Clay, who were ribbon weavers. He spent his childhood at Hood Street, Hillfields, and attended the Blue Gift school. At age 14, he was recorded as an apprentice Lithographic Printer on the 1871 census. This apprenticeship was with John W. Parbury, who at the end of that year, moved his business to larger premises at 62/63 West Orchard, opposite the Market Hall. James went on to work for all of Coventry's leading printers and at the time of his death, was employed as a Confidential Clerk for C. A. Gray & Son, Printers, Broadgate. He had been with them for 23 years.

He married Hannah Elizabeth Porter, from Walsgrave, at Vicar Lane Chapel on 7th April 1883, and they had a daughter called Alice Evelyn. Hannah died aged 40 on 12th November 1895 at their home, 5 Sibford Terrace, Croft Road. In the 1901 census, it appears that James had remarried. His wife is recorded as Elizabeth, aged 42. Her birthplace appears to be Caistor, Lincolnshire. In June 1898, the committee of the Warwick Road Congregational Church's Pleasant Sunday Afternoon group presented him with a handsome Coventry made silver watch and chain to mark the occasion of his marriage, which indicates the wedding must have taken place around that time. I think Elizabeth's maiden name may have been Nobbs. The 1911 census has James as a boarder living at 156 Broomfield Road, and says he is a widower. This would suggest that Elizabeth had sadly passed away but exact details of this are hard to find.

While printing was his profession, his real passion lay in education and the wellbeing of his fellow citizens. He served on the Coventry School Board, introduced the Pleasant Sunday Afternoon movement to the city in 1892, and was heavily involved with the Co-operative Society, particularly with education.

In 1924, he was presented with an illuminated address, a cheque for one hundred guineas and an easy chair at the Co-operative Assembly Hall. The text of the address read:

Presented to James Clay Esq. The members of the Coventry and District Co-operative Society, Ltd., desire to place on record their appreciation of the valuable services you have rendered to the Co-operative movement locally, for close on forty years, especially during the period 1917-1924, when you carried out the arduous duties of President of the Society. The members feel that you have freely given your time and labour for the good of the Society as a whole, and it is their earnest wish that, having retired from such an important post, your remaining years may be blessed with that happiness and comfort which should be the reward of faithful service.

His burial took place at Kenilworth cemetery on the August 30th and was so well attended that only half the number of mourners, many of whom were from local Co-operative societies, were able to fit inside the cemetery chapel. Wreaths included those from his daughter and son-in-law, Alice and Len Marsh, his granddaughters Margaret and Dorothy, and one from the staff of the Lounge Cafe, (8 Hertford Street) which may have been the cafe that he met his friend at every Friday.

In November 1939, a memorial service took place at Potters Green Congregational Church which he and his first wife had been associated with in their younger days. Mr. W. H. Oliver, Coventry Diocesan Missioner, who had first met him 22 years previously, gave a speech paying tribute to James, which included:

Nobody who ever heard Mr. Clay speak, could deny that he was a man possessed of a kindly soul, gentle and courteous, equipped with a knowledge that he was always pleased to pass on to others. He often stated that whatever talent he had was gained as a result of hard work, perseverance, and sheer ability to be up and doing. He was a trusted and far-seeing administrator, utterly fearless in his expression of opinion, clean, straight through and through, every inch a man, his sincerity undoubted and unchallenged.

Two other people died later with the bombing being said to have played a part in their deaths.

Harold Murdock, aged 43, of 17 Duncroft Avenue, was a tailor. Originally from Fraserburgh, Scotland, he was married to Jean (née Gray) and they had a son, also called Harold. He spent a number of days in hospital after suffering injuries in the explosion to his face, legs, buttocks, lower part of his body and hearing - which left him "stone deaf". He was off work until November and gave up working altogether in March 1940 when he developed a nervous disposition. From then on he stayed in his bed until he died on 16th April.

At the inquest it was stated that his death was the result of advanced pulmonary tuberculosis and a verdict of "Death from natural causes" was recorded. Harold was said to be ill but in moderate health before the explosion, however, the coroner did note that the injuries and terrible experience he went through may well have accelerated his death.

Walter Givens, a prominent Trade Unionist, died suddenly at his home, 25 Bates Road, on Thursday 31st August. Aged 64, he was found face down in his garden and confirmed dead at Coventry and Warwickshire Hospital. He was close to Broadgate when the explosion occurred and his trade union colleagues said he displayed obvious signs of shock that evening. They felt this, combined with his long working hours, had caused his death. The previous day he left a meeting of shop stewards at 11 p.m. His wife was away in Skegness at the time of his death.

"Death from natural causes" was the official verdict of the coroner, W. C. Iliffe, with a doctor stating that he died due to heart failure from coronary thrombosis.

Walter had been Secretary of the Coventry District of the Amalgamated Engineering Union for the past 25 years. Originally from Leeds, he and his wife Henrietta Elizabeth Givens (née Atkinson), also born in Leeds, are recorded on the 1901 census as living at 16 Gordon Street, Coventry. Both were heavily involved in social justice activism. In July 1920, Henrietta was appointed by the Lord Chancellor as Coventry's first ever female Justice of the Peace. Walter served as a City Councillor for a time in the early 1920s, representing Hearsall Ward, and in December 1935, Henrietta was elected unopposed for Radford Ward. She went on to hold many prominent positions on the Council, such as being Chair of the Housing Committee from 1945-1949. She passed away on 25th February 1959 aged 84. Givens House in Spon End is named after her.

n addition to the dead some 70 others were injured including 12 seriously. Most were treated at the Coventry & Warwickshire Hospital. Twelve blood donors were called on following the explosion and were praised for their quick attendance at the hospital. One of the most severely injured was Muriel Timms, aged 15, from Gregory Avenue. She sustained concussion and horrendous leg injuries with an operation needed to remove a piece of steel from her leg. Muriel was the last of the injured to leave hospital, returning home almost six months later on 22nd February 1940.

n addition to the dead some 70 others were injured including 12 seriously. Most were treated at the Coventry & Warwickshire Hospital. Twelve blood donors were called on following the explosion and were praised for their quick attendance at the hospital. One of the most severely injured was Muriel Timms, aged 15, from Gregory Avenue. She sustained concussion and horrendous leg injuries with an operation needed to remove a piece of steel from her leg. Muriel was the last of the injured to leave hospital, returning home almost six months later on 22nd February 1940.

In the immediate aftermath of the attack many alternative claims of what caused the explosion were mooted by people who witnessed it. Some made reference to an aircraft that had been seen overhead and believed that an air raid had been carried out marking the start of the war. Others claimed that lorries carrying T.N.T. had driven through the area moments earlier and one must have exploded. Some spoke of a second explosion, with claims that another device was planted on the clock above the H. Samuel store which emitted smoke before dropping to the floor and detonating. The police investigation soon proved all these to be false though.

Extensive damage was caused to 43 business premises in Broadgate and nearby streets. Astley's and its adjacent shops - Burton and Manfields - were hit badly as was Sketchley's directly across the road.

Alexander Ballinger was the manager of Astley's at the time. When the bomb went off he was standing near the front window. The whole frontage of the shop was blown inside and he was blown off his feet suffering several cuts to his knee, right hand, nose and head. He was clearly lucky to survive.

Robert Kinsella was another who had a lucky escape. He was walking past Burton's towards Astley's when the bomb exploded. He described what happened:

The scene of the explosion directly after the occurrence.

The scene of the explosion directly after the occurrence.

"There was a violent explosion that threw me to the ground. I picked myself up and I could see there had been terrible damage done. There were a lot of people lying about on the ground, but the first person I went to was, I believe, old James Clay, whom I picked up; I could see from his injuries he was almost dead. Of course, I then found I was bleeding very badly myself, and I went to the hospital." (He had suffered injuries to his shoulder, feet, stomach and leg.)

John Worth was sweeping the gutter outside Burton's while his colleague Bill Rowlands was sweeping the pavement outside Astley's. John was at the back of the parked saloon car (see picture) when the explosion occurred. He escaped with injuries to both arms and a thigh.

Youngsters Ian Adams and his cousin were on a bus in Corporation Street when they heard a loud boom. They were on their way to see Will Hay in a film called "Oh Mr Porter!". Reaching Broadgate minutes later, they were stopped by a police officer and discovered that what they had heard on the bus was actually a bomb going off. The road was closed and the policeman directed them via a different route to the cinema. After the film the two lads returned via Broadgate where the debris was still being cleared up. Much of it was dumped at a tip on Four Pounds Avenue. (When Ian grew up he served in the Special Branch and in early 2010 his excellent book about this I.R.A. campaign and the reaction to it, called "The Sabotage Plan", was published.)

Prior to this attack the I.R.A. had carried out numerous missions in Coventry. These included bombing telephone inspection chambers, public toilets and commercial premises. In The Sabotage Plan, Ian Adams details several attacks carried out on a single day in the spring of 1939:

On 23rd of March, there were four explosions in underground telephone inspection chambers. The first explosion, at 7.15am was in the Cheylesmore area, and shattered the glass in numerous windows. The bomb blew heavy pieces of metal into a nearby engineering works, and damaged telephone lines, lampposts, and surrounding houses. Three hours later, there was a similar explosion in a telephone junction box in Quinton Road which hurled fragments of the iron box and pieces of concrete paving over a wide area, and through the glass roof of a nearby factory. During the lunch hour there was a third explosion, in an inspection chamber of the electric transformer station at Gosford Green. John Martin, a passer-by, was injured. A fourth explosion in the afternoon, in Coundon Road, hurled a heavy iron manhole cover through the roof of St. Osburg's Roman Catholic presbytery, the church my parents and I often attended, and a Corporation bus was damaged, but nobody was injured. Balloons filled with nitric acid detonated all the bombs. The explosions disrupted many telephone lines.

In June an unexploded bomb was found near a petrol dump. They also bombed the cloakroom at Coventry Rail Station. The device exploded at 6:45 am on July 2nd. Refreshment staff had bedrooms directly above the cloakroom and eight of them had a lucky escape as fortunately the building did not collapse. They were severely shaken but escaped injury. A couple of weeks before the deadly attack on Broadgate an allotment at the rear of Armfield Street was rocked by an explosion leaving a crater two feet deep and three feet wide. A shed was blown to smithereens and two men were seen running from the scene onto Bell Green Road where they boarded a tram and escaped. The local I.R.A. unit stored explosives here and due to carelessness accidentally ignited them. This explains why the explosive used on August 25th was brought to Coventry from Liverpool via London. Up until this point the police believed that an I.R.A. unit operating from Birmingham was carrying out attacks in Coventry.

The aftermath of the Broadgate bomb led to tension between locals and the Irish community in Coventry. It was estimated that 2,000 to 6,000 Irish people were working in Coventry's factories at the time. Many left their lodgings in the city and others were asked to leave. Such was the bad feeling that the Chief Constable of Coventry Police, Captain Stanley Albert Hector, (who was from Somerset,) had to deny rumours that he was Irish. There were calls for all Irish workers to be sacked and on the day that inquests began into the deaths, thousands of workers from Armstrong Whitworth in Baginton downed tools at lunchtime and marched to Pool Meadow to protest against the I.R.A., stressing that the protest was "not directed against peaceful Irishmen." From Pool Meadow they marched through the city centre and held a rally at Market Square where their numbers were swelled by shoppers and other workers joining them. A deputation of four then met the Lord Mayor, Sidney Stringer.

Alderman Stringer had already received a memorial (petition) in the form of a book which was signed by 1,560 people. It read:

The Lord Mayor replied as politely as he could, condemning the attack as a "dastardly and cowardly act," but pointed out that in reality no one could have foreseen what was coming in a city of 250,000 people. He reassured the memorialists (petitioners) that the authorities were doing the utmost to bring those responsible to justice and thwart further attacks. He encouraged people to become special constables and said he had also discussed the setting up of civilian Ward or District Vigilance Committees with the Chief Constable. He ended his response with:

"It will be a most regrettable thing, especially at a time of national crisis, if anything in the nature of racial animosity grows up amongst us, and in making the suggestion as to the vigilance committees, the last thought in my mind is that they should act in any way unfairly towards our Irish citizens, the majority of whom, I am confident, are loyal and kind-hearted people, who abhor as much as the rest of us the things which have been happening."

Of course, the vast majority of Irish people in the city were just as appalled by the bombing as everyone else. The attack was condemned during Mass at all Catholic churches in the city the following Sunday. Father Simpson at St. Osburg's denounced the bombers as "fanatics discrediting and dishonouring Ireland" and reminded worshippers that the penalty for belonging to secret societies and plotting to destroy the state or church was ex-communication. The Midland Daily Telegraph was inundated with letters from Irish people living in Coventry expressing their disgust and horror at the attack. One such was published on Friday 1st September. It read:

Sir,

I write as an Irishman, who was on the scene of last Friday's outrage within a few minutes of its occurrence, and I cannot express the shame and rage that filled me to think that anyone calling himself an Irishman would do such a thing, and especially at such a time, when the people of Coventry, like the rest of England, were loaded down with worries and cares, not knowing at what moment war would start, and trying to make whatever little preparations they could for such a catastrophe.

Mothers and wives were saying "Goodbye," and praying to God for a speedy and safe return of their sons and husbands; anyone would think that their cup of sorrow was full enough. But not so to the Al Capones of the I.R.A. They had to add to it by killing and mutilating old men, women, and young children to the eternal shame and humiliation of the Irish race.

Therefore, as suggested by W. C. Keirnan, "An Irishman," "Ulster Irishman," and others, all decent Irishmen and women should get together and show in no uncertain manner how they feel towards the perpetrators of such a crime. If there should be any Irishman or woman so misguided as to think that the I.R.A. has the interests of Ireland or the Irish at heart - why is it condemned and outlawed by the people and government of Eire? They see it for what it is - an organisation paid and fostered by a foreign government to create strife and mistrust amongst the Irish and English; the old game of internal disruption, but a game they will lose if Irish and English people cooperate and keep a cool head.

They will find, if the occasion should arise, that the Irishmen in Coventry today are no different from those who from 1914-18, went through the hell of the Dardanelles, Mons and the mud of Flanders, side by side with the English, and who, when starving in prison camps in Germany, refused all manner of bribes and promises to turn their guns on the Allies.

It would appear from the address that the author lived next door to where the bomb was made. The idea of Irish people who were opposed to I.R.A. violence banding together to form an "Irish Union" of sorts, as the above letter makes reference to, was widespread. It was suggested that a meeting be held at St. Osburg's church. Anyone signing up for membership would have a certificate issued to them in the presence of Father Simpson. This could then be shown to employers and the local authorities to prove the bearer was a law-abiding Irish person. Members would also inform the police and local authorities about Irish people acting suspiciously.

The suggestion of a Roman Catholic led "Irish Union" provoked a response from another letter writer from Rollason Road, who described themself as a "loyal Ulster Protestant." This made clear that they and other Protestants from Ulster living in Coventry would not be attending any meetings at St. Osburg's or signing up to such a scheme - instead the author, who used the nom-de-plume of "1690," suggested a similar scheme be set up by someone from a Protestant denomination.

The outbreak of war meant neither "Union" came to fruition, which was probably a good thing, and tensions in the city soon calmed down; though the letters did foreshadow the emergence in the early 1950s of the (Irish Nationalist) Anti-Partition League and re-emergence of the Loyal Orange Institution, which had last had a presence in the city in the early 1800s when it met at The Chase public house in Gosford Street. These rival organisations held processions and their leaders regularly took issue with each other in the letter's column of the Coventry Evening Telegraph during that decade.

Thousands of Irish people worked in the city's factories during World War Two and provided an invaluable contribution to the war effort. These people followed in the footsteps of the many Irish people who worked here during World War One, when, in addition to working in the munitions factories, they notably helped build the aerodrome at Radford and new streets in that area. After World War Two ended, many thousands more made Coventry their home and played a pivotal role in rebuilding the city.

View of Broadgate after the explosion.

View of Broadgate after the explosion.

A couple of days after the attack "BUSINESS AS USUAL" signs were up in Broadgate, and though many windows were boarded up the shops were open. A newspaper report stated that £10,000 damage was caused - which would be over £500,000 in today's money. Of course, it would never be "business as usual" for the dead and their families. The Lord Mayor launched a relief fund for victims of the bombing which by the end of September had raised the substantial sum of £800.

The police initially issued press appeals saying they wished to interview Dominic Adams about the attack. An uncle of the former Sinn Fein president Gerry Adams, he was suspected of orchestrating the I.R.A. campaign in England and is believed to be the man who purchased the bicycle from Halfords while McCormack waited outside. He was very familiar with Coventry and it is highly probable that he ordered the bombing. Adams was not caught but the investigation soon led to Clara Street following the arrest of Peter Barnes in London on the same night of the Broadgate explosion. An attempt to plant a further three 'bicycle bombs' in the capital city had been thwarted in the morning and Barnes was suspected of having supplied explosives to those involved by the police. When news of the outrage in Coventry and how it was carried out reached them, they were sure he must have been involved. At 8:50 pm he arrived home to find Detective Sergeant William Hughes and some of his colleagues from the Special Branch at Scotland Yard waiting for him. When D.S. Hughes and the officers with him searched his room in a boarding house at 176 Westbourne Terrace, they found potassium chlorate in a chest of drawers and an incriminating letter in the pocket of the coat that he was wearing. Barnes had written it the previous day (August 24th) and addressed it to a man in Ireland. Luckily for the police, he had not posted it. In it he made reference to his 'job' being to move the 'S-' from place to place ("S-" meaning "stuff" - the explosives) and stated "I am after coming back from Coventry tonight 11-30 so by the time you get this the paper should have some news." Clearly he expected something dramatic to happen in the city that would make headlines.

Barnes had called at Clara Street previously on August 21st to acquaint himself with McCormack and discuss the transportation of the "stuff". During this visit, McCormack asked Brigid O'Hara to buy a suitcase for Barnes and also asked Mary Hewitt to buy two empty flour sacks. The flour sacks were purchased from Celia's on Walsgrave Road but had to be returned as they were the wrong type. Both women returned them. The suitcase was brought from Forey's Ironmongers. For reasons known only to himself - perhaps he had to account to the I.R.A. for his expenses? - Peter Barnes kept the receipts. He passed them on to his fiance Sarah Ann Keane for safekeeping and they were found by the police when they searched her home in London following his arrest. These were to prove crucial in the Coventry investigation. The owner of Celia's, Mary Cecilia Downs, was able to identify both women, and Mabel Hubbard, a shop assistant at Forey's, identified Brigid O'Hara as the purchaser of the suitcase.

Chief Inspector Cyril George Boneham of the Coventry City Police led the local investigation. He and his team were assisted by Special Branch detectives. On August 28th, Chief Inspector Boneham and Detective Inspector Sydney Barnes of Special Branch led a search of 25 Clara Street. Tools suitable for bomb making, screws, bolts, insulating tape, labels from a battery and crucially a brass setter for the back of an alarm clock were found. This setter, or key, appeared to be new and did not fit any clock in the house. The occupants were detained and initially released while deportation orders were applied for. On September 2nd they were arrested under the Prevention of Violence (Temporary Provisions) Act. As the investigation proceeded and clear evidence of bomb making at the house emerged those being held were then charged under the Explosive Substances Act, 1883. Later that month, on the 27th, after a thorough police investigation and careful consideration, the Public Prosecutor decided that the facts justified a charge of murder against all five people being held. The charge was limited to the murder of Elsie Ansell and not the other four victims.

he trial began on Monday 11th of December at the Warwick Assizes, Victoria Courts, Birmingham. One crucial person was missing - the man who actually built and planted the bomb. He was never captured. It was acknowledged that those in the dock - James McCormack, Peter Barnes, Joseph Hewitt, Mary Hewitt and Brigid O'Hara - had not made or planted the bomb, but as it was believed they had all played an active part in a conspiracy that could clearly endanger life it was a murder charge they faced, and consequently the hangman's noose if found guilty. On Friday 14th December, McCormack, who was tried under his alias of James Richards, and Peter Barnes were found guilty by the jury and convicted of murder. After the guilty verdicts were passed, James McCormack gave this response:

he trial began on Monday 11th of December at the Warwick Assizes, Victoria Courts, Birmingham. One crucial person was missing - the man who actually built and planted the bomb. He was never captured. It was acknowledged that those in the dock - James McCormack, Peter Barnes, Joseph Hewitt, Mary Hewitt and Brigid O'Hara - had not made or planted the bomb, but as it was believed they had all played an active part in a conspiracy that could clearly endanger life it was a murder charge they faced, and consequently the hangman's noose if found guilty. On Friday 14th December, McCormack, who was tried under his alias of James Richards, and Peter Barnes were found guilty by the jury and convicted of murder. After the guilty verdicts were passed, James McCormack gave this response:

"My lord, before you pass sentence I have something to say. I wish to state, my lord, before you pass sentence of death on me, I wish to thank sincerely the gentlemen who have defended me during my trial and I wish to state that the part I took in these explosions since I came to England I have done for a just cause. As a soldier of the Irish Republican Army I am not afraid to die, as I am doing it for a just cause. I say in conclusion, God bless Ireland and God bless the men who have fought and died for her. Thank you, my lord."

Peter Barnes said:

"I would like to say as I am going before my God, as I am condemned to death, I am innocent, and later I am sure it will come out that I had neither hand, act or part in it. That is all I have to say."

The Hewitts and Brigid O'Hara were acquitted - they were later charged with the murder of the other four people who were killed and five counts under the Explosive Substances Act and all three pleaded not guilty. No evidence was offered by the prosecution on the murder charge and the judge ordered the jury to return a formal verdict of not guilty. The women were discharged while Joseph Hewitt was remanded in custody. At the Old Bailey in London on 6th February 1940 he was charged with maliciously causing an explosion and having explosive substances in his possession. No evidence was offered by the prosecution and after a verdict of not guilty by the jury he was discharged. The following day, the guilty pair - Peter Barnes and James McCormack - were executed at Winson Green Prison. An appeal against their convictions had been dismissed in January. In the very same week of the hangings the mother of Elsie Ansell died at the early age of 49. Laura Ansell was being cared for by the mother of Harry Davies, her late daughter's fiance. Mrs Davies said that she never recovered from the loss of Elsie and died of a broken heart.

The hangings of McCormack and Barnes caused outrage in Ireland and other parts of the world. It was felt unjust that as they had not made or planted the bomb they should die because of the actions of another person. Appeals for clemency were ignored. Public mourning was observed and flags flew at half-mast in Ireland on the day of the executions.

A crowd gathers in Broadgate soon after the incident. The actual site of the bomb is just out of shot to the left.

A crowd gathers in Broadgate soon after the incident. The actual site of the bomb is just out of shot to the left.The actual bomber was never betrayed by those who appeared in court charged with the murder of Elsie Ansell. McCormack and Barnes understandably refused to name their comrade, while the others, who would not have been told his name, referred to him simply as "the strange man". It appears he came to Coventry specifically for this task and was not part of the local I.R.A. unit. Since this article was originally published in 2009, he has been widely named as Joby O'Sullivan, who was a native of Cork. In an interview given before his death to an Irish journalist, O'Sullivan claimed that he was responsible for the attack and that the real target for the bomb was Coventry's main police station. He said the bicycle kept getting stuck in tram lines so he abandoned it before making his escape to the railway station. If true, this means he actually cycled past a number of turn-offs for the police station before reaching Broadgate. If he was lost he makes no mention of it which would be a more plausible explanation than being impeded by tram lines. In other interviews given in the late 1960s, O'Sullivan said that he left the bomb exactly where he was asked to, and claims he told his superior that there would be loss of life but the response was that this did not matter. The lack of consistency in these various interviews suggests a very guilty conscience at what happened, and, in my opinion, they are clearly attempts to distance himself from his role in the atrocity. O'Sullivan was described as a "psychopath" by one leading author on Irish Republicanism and according to others spent a lot of time in mental health institutions.

Other Republican sources state the target was supposed to be an electricity generating station. Another suggestion is that the attack was quite deliberate and designed to show Nazi Germany the capabilities of the I.R.A. At the time the organisation's leadership was trying to persuade Germany to form a mutual alliance with them to fight the British. There is a wealth of speculation out there but the simple fact remains that a high explosive no warning bomb was left in the busiest shopping street in the city, supposedly contrary to I.R.A. instructions to not endanger civilians. The bomber made a conscious decision to do this and must have known the likely outcome of his actions.

This particular badly timed and ill-judged I.R.A. campaign against Britain is often said to have petered out following the carnage in Coventry, but in fact there were a further 42 incidents attributed to the I.R.A., with the last bomb exploding on a rubbish dump in London on 18th March 1940.

After their acquittals, the Hewitts and Brigid O'Hara were deported from England and returned to Belfast.

A memorial was erected to James McCormack and Peter Barnes in Banagher, County Offaly in 1963. In July 1969, their remains were moved from the grounds of Winson Green prison and re-interred in Ballyglass cemetery, Mullingar, County Westmeath. 15,000 people attended. To this day, both men continue to be remembered by the Republican movement in Ireland and are regarded as martyrs.

The Lord Mayor of Coventry, Cllr Michael Hammon, and the Very Reverend John Witcombe, Dean of Coventry, at the unveiling of the memorial to remember those who died on 25th of August 1939.

The Lord Mayor of Coventry, Cllr Michael Hammon, and the Very Reverend John Witcombe, Dean of Coventry, at the unveiling of the memorial to remember those who died on 25th of August 1939.

On the 14th of October 2015 a memorial stone was unveiled in Coventry to the victims of the attack. It is located on Unity Lawn in the grounds of the Cathedral.

The dedication service was simple but dignified and helped bring a degree of closure to the victims' families who have never forgotten their loved ones. Many of them were in attendance and they laid single white roses at its base.

Coventry City Council paid for the memorial and the Cathedral, which is renowned throughout the world as a centre of peace and reconciliation, facilitated its location. It is a short distance from Broadgate. Given that it is almost impossible to determine the exact site of the blast (somewhere near the Lady Godiva statue, see below for Rob Orland's comparison of contemporary and modern maps) and the fact that Broadgate tends to be re-modelled every few years, it was felt by the families that Unity Lawn would be a better location.

The original version of this article had highlighted the lack of a memorial and led to many people questioning why this was the case. One person who read it and subsequently got in touch was BBC News Online journalist Jenny Harby. In 2014, on the 75th anniversary of the attack, her powerful article entitled "Coventry IRA bombing: The 'forgotten' attack on a British city" was published on the BBC News website. Jenny did an enormous amount of work behind the scenes with the victims families and relevant authorities which ultimately led to unanimous agreement for a memorial to be erected. BBC Coventry & Warwickshire also regularly kept the story in the public eye.

The remains of the bicycle pictured in 2010.

The remains of the bicycle pictured in 2010.Elsewhere in Coventry, the remains of the bicycle and other evidence gathered after the explosion can be viewed at the excellent Police Museum which is located in Coventry Council House. This is open Thursdays and Fridays (10 am - 2 pm) subject to the availability of the wonderful volunteers who give up their time to run it.

In June 2010, with the kind permission of the then curator, Tony Rose, I was able to photograph the remains of the bicycle at the museum's previous location in the basement of Little Park Street police station. The handlebars, front wheel and carrier basket are missing but remarkably, much of the rest of it is still intact. Some parts are dented, rusted, scratched and mangled but others bits are unscathed and look nearly new. When Mr Rose opened the cabinet I was hit by the smell of rubber and explosive. It was very sad gazing at this unwitting instrument of death and destruction and my thoughts turned to the victims. May they all rest in peace.

* * * * *

Below is a 1937 map showing the spot where the bomb detonated.

Clicking on the map will reveal where it occurred on a modern-day aerial view (courtesy of Google Maps).

* * * * *

Marie Jones, Jane Bant and Betty Rowlands - many thanks.

Sheila Medlock.

Tony Rose of Coventry Police Museum & West Midlands Police for permission to photograph and use the image of the remains of the bicycle.

Ian Adams - for permission to quote from "The Sabotage Plan".

Rob Orland - additional images & web page arrangement.

Books:

"Trial of Peter Barnes and Others" (The I.R.A. Coventry Explosion of 1939). Edited by Letitia Fairfield.

"Coventry IRA Bombing: The 'forgotten' attack on a British city" by Jenny Harby. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-coventry-warwickshire-28191501

"The Devil's Deal: The IRA, Nazi Germany and the Double Life of Jim O'Donovan" by David O'Donoghue.

The British Newspaper Archive & Ancestry UK websites.

Newspapers:

The Midland Daily Telegraph, Coventry Herald, Coventry Standard, Rugby Advertiser, Leicester Evening Mail, Glamorgan Gazette, Fraserburgh Herald.

On the 26th February 2012 Simon was given the chance to speak about this article to Mollie Green on BBC Radio Coventry & Warwickshire. The clip is available on the left.

Website by Rob Orland © 2002 to 2026